Sagrada Família

By Kate Busby

© Bastiaan de Vrijer

This is the tale of a blue-eyed man with a thousand-yard stare, who scuttled around Barcelona with a collection tin to complete a dream. A dream that, 130 years later, remains unfinished, but has evolved from a dingy plot of land in the Eixample to the monstrously kitsch house of worship that we now know as the Sagrada Família. And that blue-eyed man? Antoni Gaudí i Cornet: architect, eccentric and genius. A person that wealthy Catalans would cross the road to avoid.

Gaudí did not conceive the idea for the Sagrada Família, nor was he the first choice to work on it. The founder was, in fact, a bookseller by the name of Bocabella who, legend has it, dreamt of finding an architect with “piercing blue eyes” and then met 31-year old rising star Gaudí after the resignation of his first builder. It was an appointment that proved fortuitous, as Bocabella’s idea for a “Cathedral of the Poor” became Gaudí’s ultimate, living masterpiece – and which made both him and his work singularly iconic of the city.

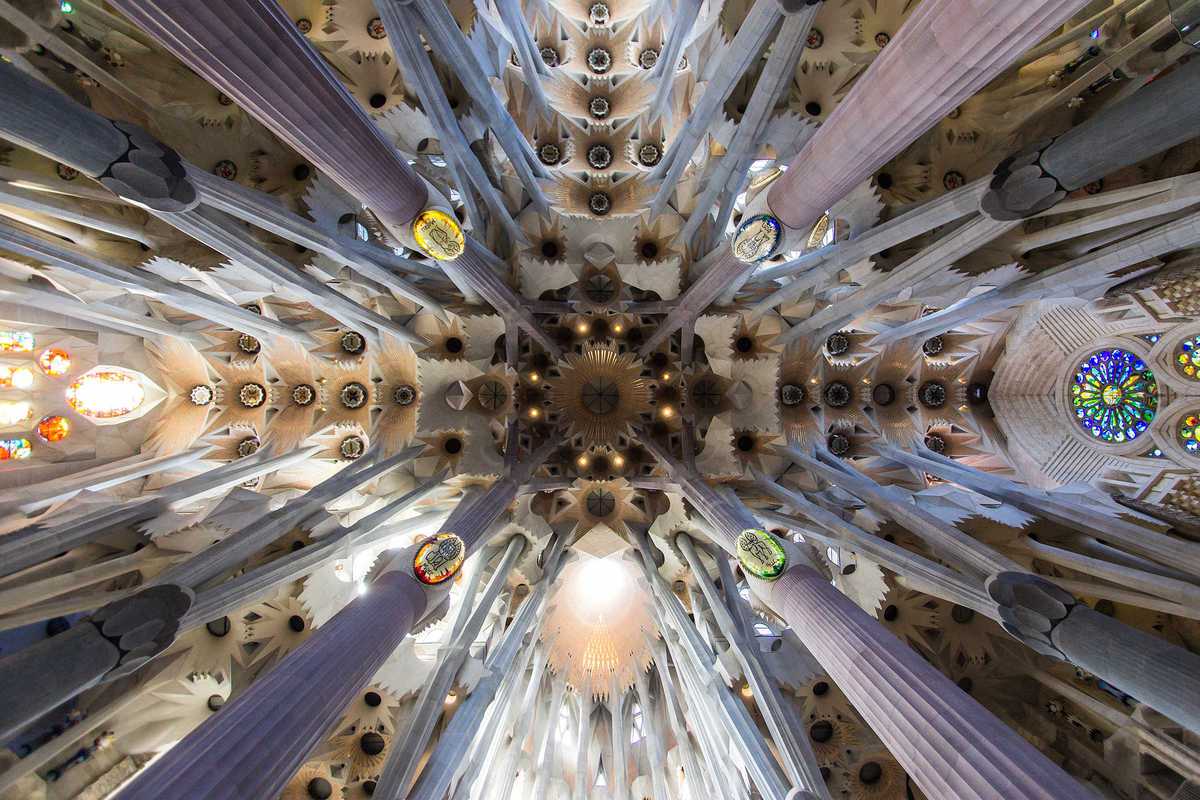

Forty years of Gaudí’s life were devoted to working tirelessly on the Sagrada Família. He calculated how the journey of a leaf swirling to the ground could be converted into a 100-meter spiral staircase. And how to make the interior décor resemble a slanting, granite forest with sunset light filtering through its roof of stone leaves. He stuck gigantic, boiled sweets onto the interior pillars. His bell towers end in heaps of multicolored fruit. Dalí called it “bad taste” but loved it all the same.

The architects who have succeeded Gaudí have plenty of guidelines to go by, but critics find that the newest sections are cold, hard-edged and staid, whereas Gaudí’s approach breathes humanness and dare, faithful to the foaming, romping, spurting, dripping, drifting elements found in nature. Very little, if anything, was taboo for Gaudí. He is said to have made plaster casts of temporarily anesthetized chickens so as to recreate their likeness when later sculpted in stone. At points his designs push the envelope so far that it takes a while for any of them to make sense. The Nativity Facade, for example, is so bristling and intricate that any more than a couple of glances will provoke dizziness and turn weaker stomachs.

Such rampant creativity in a holy place could only exist in free-spirited Barcelona but still, it begs the question: how was someone allowed to do that in a Roman Catholic church? You can barely imagine the Pope consecrating the place in 2010 without smiling a little, in disbelief as much as awe, at what this extraordinary Catalan architect was capable of, and all in the name of God. For Gaudí was indeed a devout man who, according to biographer Gijs van Hensbergen, existed on an ascetic diet of lettuce leaves dipped in milk. When asked if it bothered him to not see the work completed in his lifetime, Gaudí simply replied, “My client” – referring to God – “is not in a hurry.”

So, still incomplete, still evolving, the Sagrada Família is the epitome of ephemera. One day it is like this, the next day, different. People around the world visit impressive churches all the time, but it is quite something to walk around this particular church and see the staff not changing the flowers but actually making enormous structural alterations – attaching fixtures, carving facades and unveiling entire statues to be enjoyed by the visitors of tomorrow. Religious feeling can be found somewhere amid the spectacle, but it is not the focus. People tend less to pray in the Sagrada Família than immerse themselves in a house of living art, where it feels as if just about anything could happen.

Today, for example, I am sitting inside the basilica on what must be the coldest morning of the year, with barely a tourist in sight. Even so, the sounds of hammers, cameras and workers wheeling large objects on trolleys gives the impression of a buzzing movie set. A gaggle of Cistercian monks pass by. I stop one of them and ask why he has chosen this particular day to visit. “Our order has donated money for one part of the basilica’s construction. Today’s the inauguration,” he explains.

You would be mistaken for thinking that such an epic church would have an official source of funding, but no. The Sagrada Família is the ultimate startup, based entirely on donations. If the money runs out, building stops, and everyone loses their job. Curiously, the majority of donations come, according to art historian Robert Hughes, from the Japanese. He thoughtfully notes that “the Sagrada Família is the first Catholic temple whose bacon was ever saved by Shinto tourism.”

Back inside the main area of worship, another eccentric design comes in the form of a crucified Jesus suspended from a large beach umbrella decorated with glass grapes and white fairy lights. While almost too ironic, there is still something sincere about this Christ, dead and at peace among references to sun, booze and fun. The aesthetic at work here is none too dissimilar to Baz Luhrmann’s remake of Romeo and Juliet in which the simple, beautiful lovers oscillate innocently around each other while surrounded by loud-mouthed, parasitical urbanites. In both cases, something noble and age-old is alive in the tackiness of a modern setting.

Maybe there is not much dignity in the world we live in today, but it is what we have, and to avoid it is quite simply to lie. Gaudí embraced it, as much as he embraced religion, and tried to pack in as much as he could of both into 170 vertical meters of granite. The edifice as a whole resembles an erupting, mutating skin complaint on the face of Barcelona. But in spite of its flagrant ugliness, the Church of the Holy Family is utterly breathtaking and unforgettable.